vignettes/a_09_linear_model.Rmd

a_09_linear_model.Rmdtitle: “04. fMRI Linear Model (GLM)” author: “Bradley R. Buchsbaum” date: “2026-01-28” output: rmarkdown::html_vignette vignette: > % % % —

Introduction to fMRI Linear Models

Statistical analysis of fMRI data typically involves fitting a linear

model to each voxel’s time series. This approach, often called the

General Linear Model (GLM), estimates how much each experimental

condition contributes to the observed signal. The fmrireg

package provides a flexible framework for:

- Modeling the hemodynamic response to experimental stimuli

- Accounting for baseline trends and noise

- Estimating condition-specific effects

- Computing contrasts between conditions

- Testing statistical hypotheses about brain activity

Thread usage in internal routines can be adjusted globally. Set

options(fmrireg.num_threads = <n>) or the environment

variable FMRIREG_NUM_THREADS before loading the package to

control how many threads RcppParallel uses.

This vignette demonstrates how to conduct a complete linear model

analysis using the fmrireg package, from data simulation to

statistical inference.

Simulating a Dataset for Analysis

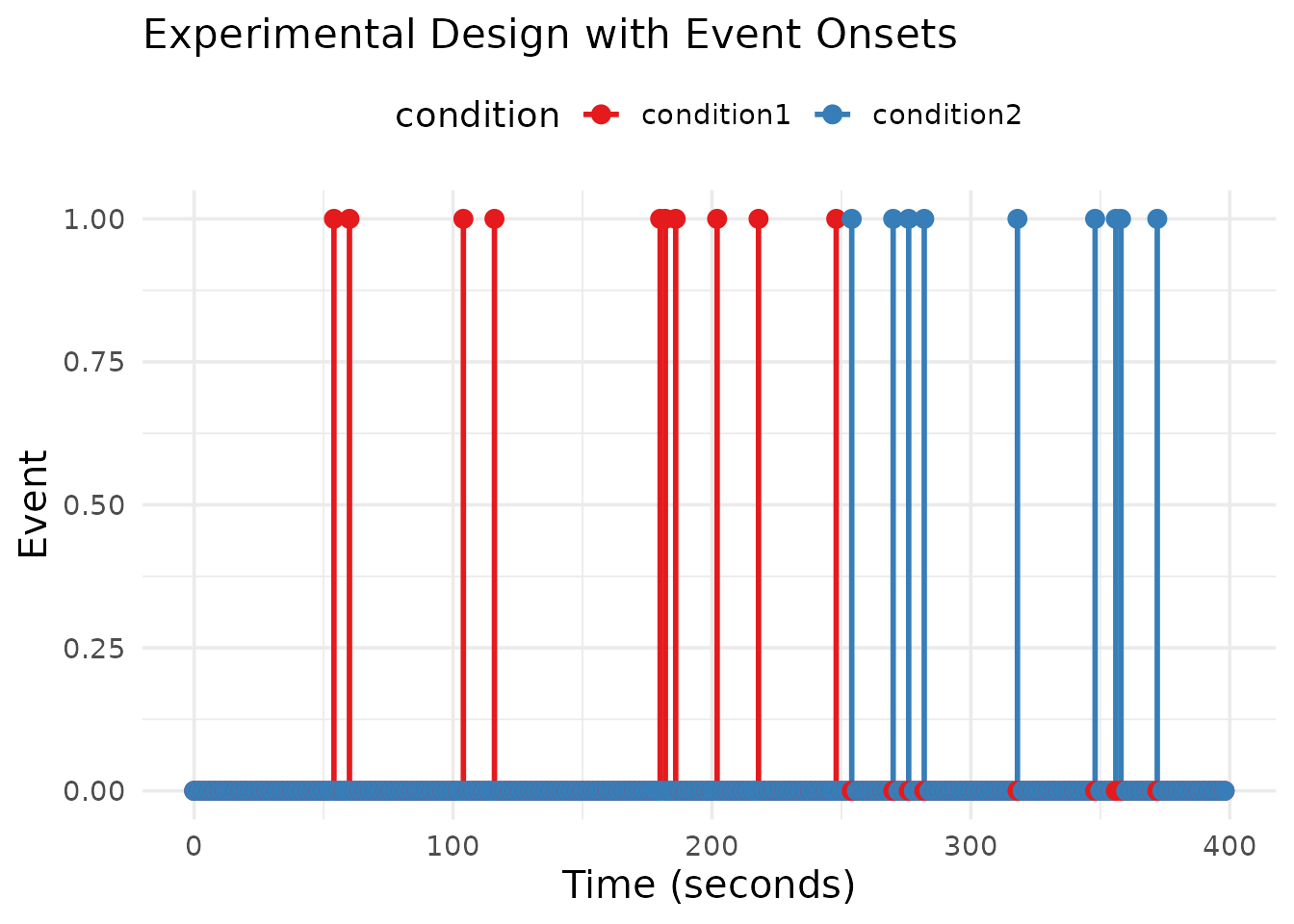

First, let’s create a realistic fMRI dataset with known parameters. We’ll simulate a simple experiment with two conditions that have different amplitudes.

# Create an experimental design with two conditions

# Condition 1: 10 events with amplitude 1.0

# Condition 2: 10 events with amplitude 2.0

# Define parameters

TR <- 2 # Repetition time (2 seconds)

run_length <- 200 # 200 timepoints per run = 400 seconds

nruns <- 1 # Number of runs

# Create an event table

run_id <- rep(1, 20)

condition <- factor(rep(c("condition1", "condition2"), each = 10))

onset_times <- sort(runif(20, min = 10, max = 380)) # Random onsets between 10s and 380s

event_table <- data.frame(

run = run_id,

onset = onset_times,

condition = condition

)

# Display the experiment design

kable(head(event_table), caption = "First few rows of the experimental design")| run | onset | condition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53.47032 | condition1 |

| 1 | 59.82664 | condition1 |

| 1 | 104.50866 | condition1 |

| 1 | 115.87163 | condition1 |

| 1 | 179.36446 | condition1 |

| 1 | 181.04834 | condition1 |

# Create a sampling frame

sframe <- sampling_frame(blocklens = run_length, TR = TR)

# Visualize the experimental design

event_df <- data.frame(

time = seq(0, (run_length-1) * TR, by = TR),

condition1 = rep(0, run_length),

condition2 = rep(0, run_length)

)

# Mark event onsets in the timeline

for (i in 1:nrow(event_table)) {

timepoint <- which.min(abs(event_df$time - event_table$onset[i]))

if (event_table$condition[i] == "condition1") {

event_df$condition1[timepoint] <- 1

} else {

event_df$condition2[timepoint] <- 1

}

}

# Convert to long format for plotting

event_long <- event_df %>%

pivot_longer(cols = -time, names_to = "condition", values_to = "onset")

# Plot the experimental design

ggplot(event_long, aes(x = time, y = onset, color = condition)) +

geom_segment(aes(xend = time, yend = 0), linewidth = 1) +

geom_point(size = 3) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(legend.position = "top",

text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.title = element_text(size = 15),

plot.title = element_text(size = 16)) +

labs(title = "Experimental Design with Event Onsets",

x = "Time (seconds)",

y = "Event") +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "Set1")

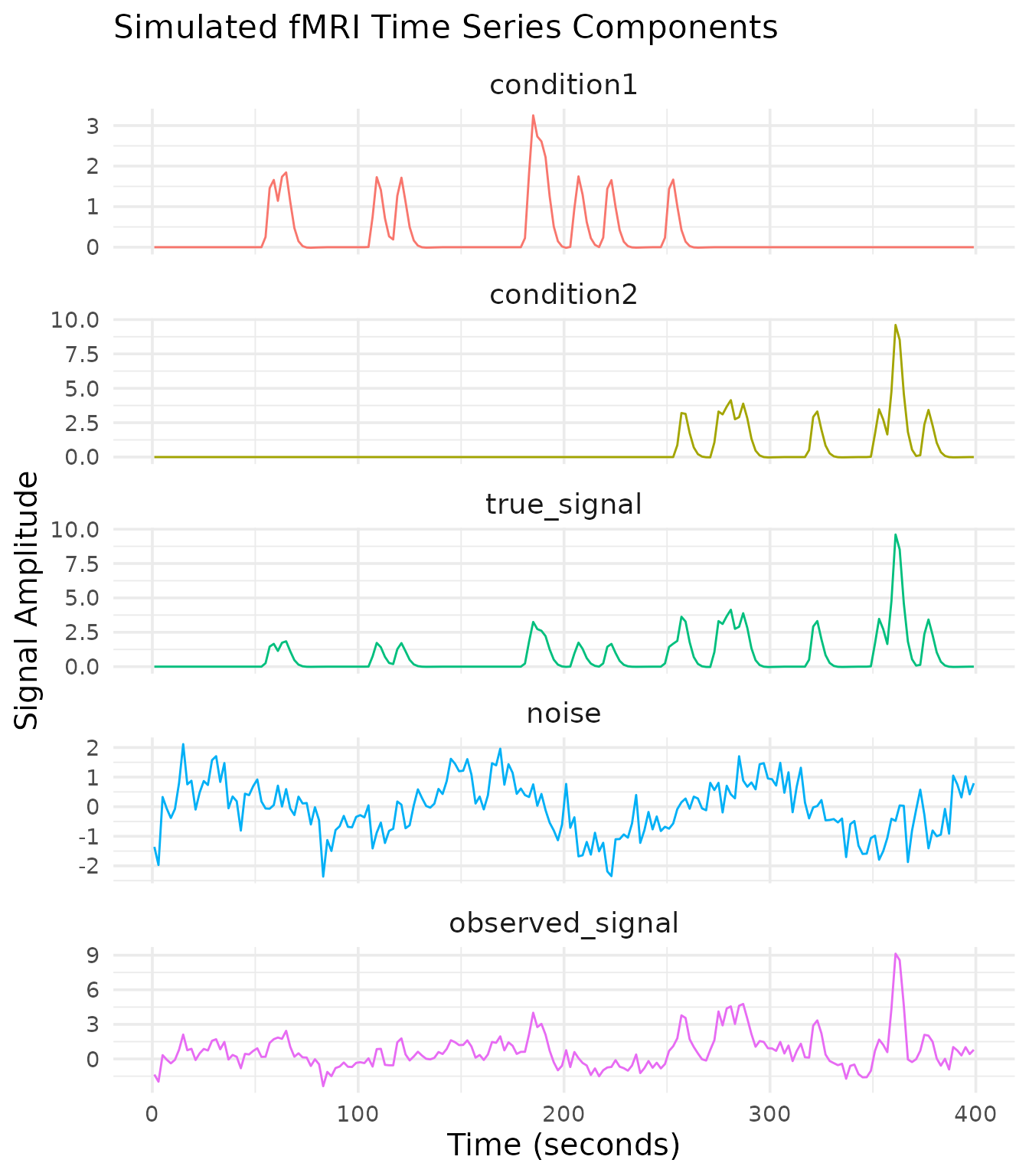

Now that we have our experimental design, let’s simulate the fMRI time series. We’ll create signals for each condition with different amplitudes, add noise, and combine them into a dataset.

# Simulate the true BOLD signals for each condition

# First, convert our events to global indices

global_onsets <- global_onsets(sframe, event_table$onset, blockids(sframe)[event_table$run])

# Create regressors for each condition

condition1_indices <- which(event_table$condition == "condition1")

condition2_indices <- which(event_table$condition == "condition2")

reg1 <- regressor(global_onsets[condition1_indices], hrf = fmrihrf::HRF_SPMG1, amplitude = 1.0)

reg2 <- regressor(global_onsets[condition2_indices], hrf = fmrihrf::HRF_SPMG1, amplitude = 2.0)

# Sample time points

time_points <- samples(sframe, global = TRUE)

# Evaluate regressors at each time point

signal1 <- evaluate(reg1, time_points)

signal2 <- evaluate(reg2, time_points)

# Combine signals (this is the "true" signal without noise)

true_signal <- signal1 + signal2

# Create noise with temporal autocorrelation and drift

noise <- simulate_noise_vector(

n = length(time_points),

TR = TR,

ar = c(0.7), # Stronger AR(1) coefficient to accentuate autocorrelation

ma = numeric(0), # Pure AR structure keeps the example simple

drift_freq = 1/128, # Slow drift

drift_amplitude = 1, # Moderate drift amplitude

physio = TRUE, # Include physiological noise

sd = 0.5 # Noise standard deviation

)

# Create the observed signal by adding noise

observed_signal <- true_signal + noise

# Create a data frame for visualization

signal_df <- data.frame(

time = time_points,

true_signal = true_signal,

noise = noise,

observed_signal = observed_signal,

condition1 = signal1,

condition2 = signal2

)

# Create a matrix dataset for the model fitting

simulated_data <- matrix(observed_signal, ncol = 1)

dataset <- fmridataset::matrix_dataset(

datamat = cbind(simulated_data, simulated_data * 0.8, simulated_data * 0.6), # Three "voxels" with varied signal strength

TR = TR,

run_length = run_length,

event_table = event_table

)

# Visualize the signals

signal_long <- signal_df %>%

select(time, condition1, condition2, true_signal, noise, observed_signal) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = -time, names_to = "component", values_to = "signal")

# Set the factor levels for better plotting order

signal_long$component <- factor(signal_long$component,

levels = c("condition1", "condition2", "true_signal", "noise", "observed_signal"))

# Plot signals

ggplot(signal_long, aes(x = time, y = signal, color = component)) +

geom_line() +

facet_wrap(~component, ncol = 1, scales = "free_y") +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(legend.position = "none",

text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.title = element_text(size = 15),

plot.title = element_text(size = 16),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14)) +

labs(title = "Simulated fMRI Time Series Components",

x = "Time (seconds)",

y = "Signal Amplitude")

Our simulated dataset now contains:

- Condition-specific signals with known amplitudes (1.0 and 2.0)

- Realistic noise with temporal autocorrelation, drift, and physiological components

- Multiple “voxels” with varying signal strengths

- A complete event table with condition labels and onset times

Fitting a Linear Model

Now we can fit a linear model to our simulated data using the

fmri_lm function. We need to specify:

- The formula describing the experimental effects

- The block structure of the data

- The dataset

# Fit a linear model

model <- fmri_lm(

formula = onset ~ hrf(condition), # Model experimental effects

block = ~ run, # Block structure

dataset = dataset, # Our simulated dataset

strategy = "chunkwise", # Processing strategy

nchunks = 1 # Process all voxels at once

)

# Print a summary of the model

model##

## ==================================

## fmri_lm_result

## ==================================

##

## Model formula:

## ~ onset hrf(condition)

##

## Fitting strategy: chunkwise

##

## Baseline parameters: 4

## Design parameters: 2

## Contrasts: None

##

## Use coef(...), stats(...), etc. to extract results.

##

## Accounting for Temporal Autocorrelation

The simulated noise contains AR(1) structure. We can ask

fmri_lm to apply a fast AR(1) prewhitening step by setting

cor_struct = "ar1". This estimates the AR coefficient from

an initial OLS fit, whitens the data and design matrix, and refits the

GLM.

With stronger temporal autocorrelation in the simulated noise, the prewhitened model recovers tighter standard errors than OLS.

model_ar1 <- fmri_lm(

formula = onset ~ hrf(condition),

block = ~ run,

dataset = dataset,

strategy = "chunkwise",

nchunks = 1,

cor_struct = "ar1",

cor_iter = 2 # Iterate to refine the AR(1) estimate

)

# Compare standard errors (first few voxels)

se_ols <- standard_error(model)

se_ar1 <- standard_error(model_ar1)

head(round(cbind(OLS = se_ols[[1]], AR1 = se_ar1[[1]]), 4))## OLS AR1

## [1,] 0.1170 0.0943

## [2,] 0.0936 0.0604

## [3,] 0.0702 0.0340

# Inspect the estimated AR coefficient (shared across voxels in this example)

model_ar1$ar_coef[[1]]## [[1]]

## [1] 0.7065745The AR(1) model now estimates a non-zero autoregressive coefficient and produces notably smaller standard errors than the plain OLS fit, illustrating how prewhitening improves efficiency when temporal autocorrelation is present.

The cor_struct argument also accepts "arp"

for higher-order autoregressive models. This setting models AR

coefficients only (no moving-average terms).

Handling Outliers with Row-Wise Robust Fitting

Real fMRI runs sometimes contain entire time points corrupted by

motion or scanner artifacts. The fmri_lm function can

mitigate their impact by enabling row-wise robust weighting. When

robust = TRUE, an Iteratively Reweighted Least Squares loop

down-weights frames with large residuals. The robust_psi

argument selects the weighting function and robust_max_iter

controls the number of iterations.

model_robust <- fmri_lm(

formula = onset ~ hrf(condition),

block = ~ run,

dataset = dataset,

strategy = "chunkwise",

nchunks = 1,

robust = TRUE,

robust_psi = "huber",

robust_max_iter = 2

)

se_robust <- standard_error(model_robust)

head(cbind(OLS = se_ols[[1]], Robust = se_robust[[1]]))## OLS Robust

## [1,] 0.11701370 0.06946794

## [2,] 0.09361096 0.06946794

## [3,] 0.07020822 0.06946794Robust fitting guards against outlier time points but will not correct voxel-specific spikes. In this simulated example the Huber weights inflate the standard errors slightly, reflecting the additional uncertainty introduced by potential outliers. P-values rely on a robust residual scale and should be interpreted as approximate.

Extracting Model Results

Let’s extract and visualize the results from our linear model.

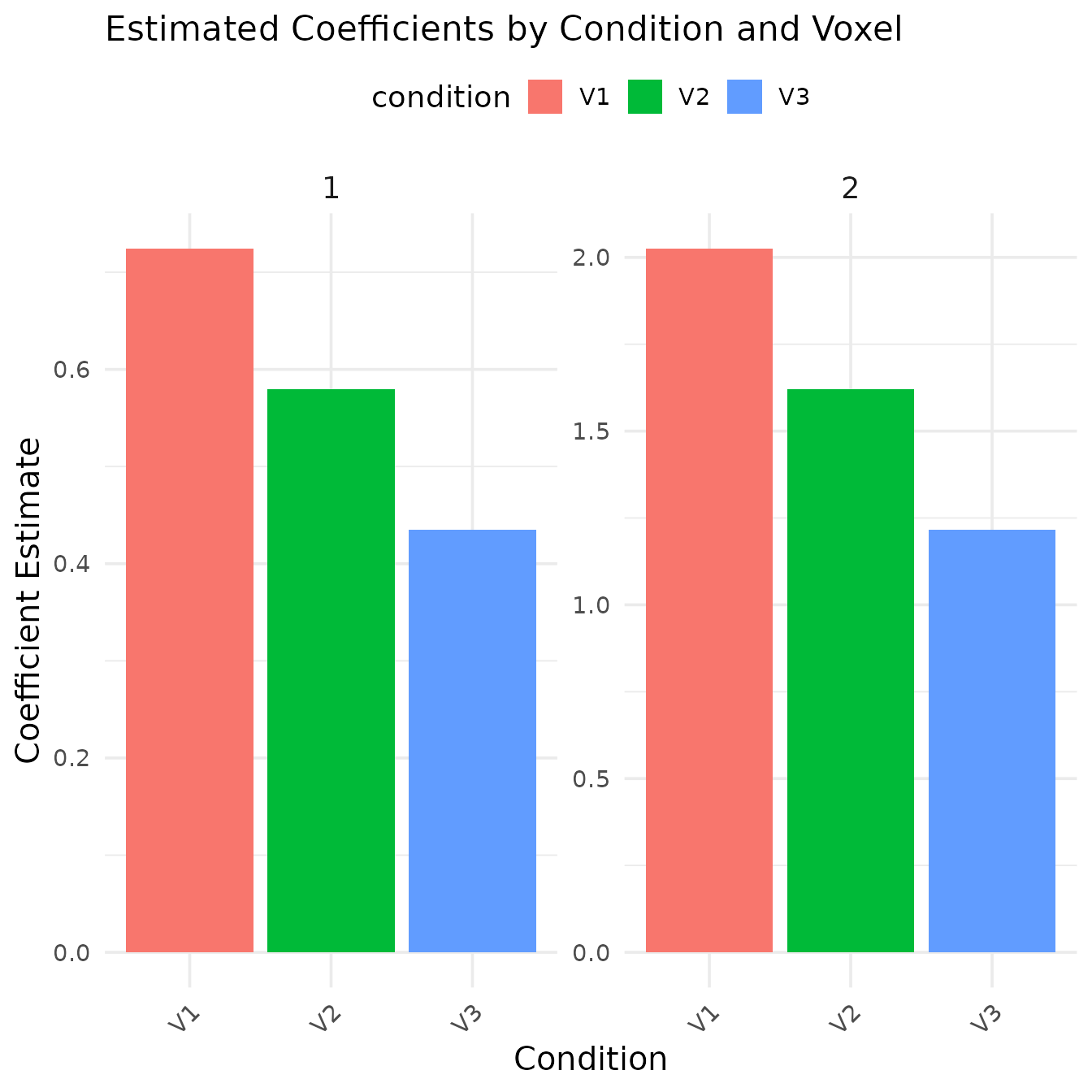

1. Coefficient Estimates

# Extract coefficient estimates

beta_estimates <- coef(model)

kable(beta_estimates, caption = "Coefficient estimates for each condition and voxel")| condition_condition.condition1 | 0.6482899 | 0.5186319 | 0.3889739 |

| condition_condition.condition2 | 1.8880917 | 1.5104734 | 1.1328550 |

# Helper to clean condition column labels for readability

clean_condition_label <- function(x) {

x <- gsub("^conditioncondition_condition\\.", "", x)

x <- gsub("^condition_condition\\.", "", x)

gsub("\\.", " ", x)

}

# Reshape for plotting (works with both approaches)

beta_long <- as.data.frame(t(beta_estimates)) %>%

mutate(voxel_index = row_number()) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = -voxel_index, names_to = "condition", values_to = "estimate") %>%

mutate(

condition = clean_condition_label(condition),

voxel = paste0("voxel", voxel_index)

)

# Plot coefficient estimates

ggplot(beta_long, aes(x = condition, y = estimate, fill = condition)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

facet_wrap(~voxel, ncol = 3, scales = "free_y") +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(legend.position = "top",

text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.title = element_text(size = 15),

plot.title = element_text(size = 16),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1)) +

labs(title = "Estimated Coefficients by Condition and Voxel",

x = "Condition",

y = "Coefficient Estimate")

The bar plot shows the estimated coefficients for each condition across the three simulated voxels. Note that:

- Condition2 has approximately twice the amplitude of Condition1, which matches our simulation parameters

- The coefficient magnitude decreases across voxels, consistent with our multiplication factors (1.0, 0.8, 0.6)

2. T-Statistics and P-Values

estimate_stats <- tidy(model, type = "estimates") %>%

filter(grepl("condition", term)) %>%

mutate(condition = clean_condition_label(term),

voxel = paste0("voxel", voxel)) %>%

select(voxel, condition, estimate, std_error, statistic, p_value)

kable(estimate_stats, digits = 4,

caption = "Coefficient estimates with associated statistics by voxel and condition")| voxel | condition | estimate | std_error | statistic | p_value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| voxel1 | condition1 | 0.6483 | 0.1170 | 5.5403 | 0.0000 |

| voxel1 | condition2 | 0.5186 | 0.0936 | 5.5403 | 0.0000 |

| voxel2 | condition1 | -0.5550 | 0.7480 | -0.7420 | 0.4590 |

| voxel2 | condition2 | -0.4440 | 0.5984 | -0.7420 | 0.4590 |

| voxel3 | condition1 | -0.7525 | 0.3992 | -1.8851 | 0.0609 |

| voxel3 | condition2 | -0.6020 | 0.3193 | -1.8851 | 0.0609 |

The t-statistics quantify the reliability of the estimated effects. Higher absolute t-values indicate more reliable estimates. In our simulation, all conditions in all voxels show significant activity (p < 0.05).

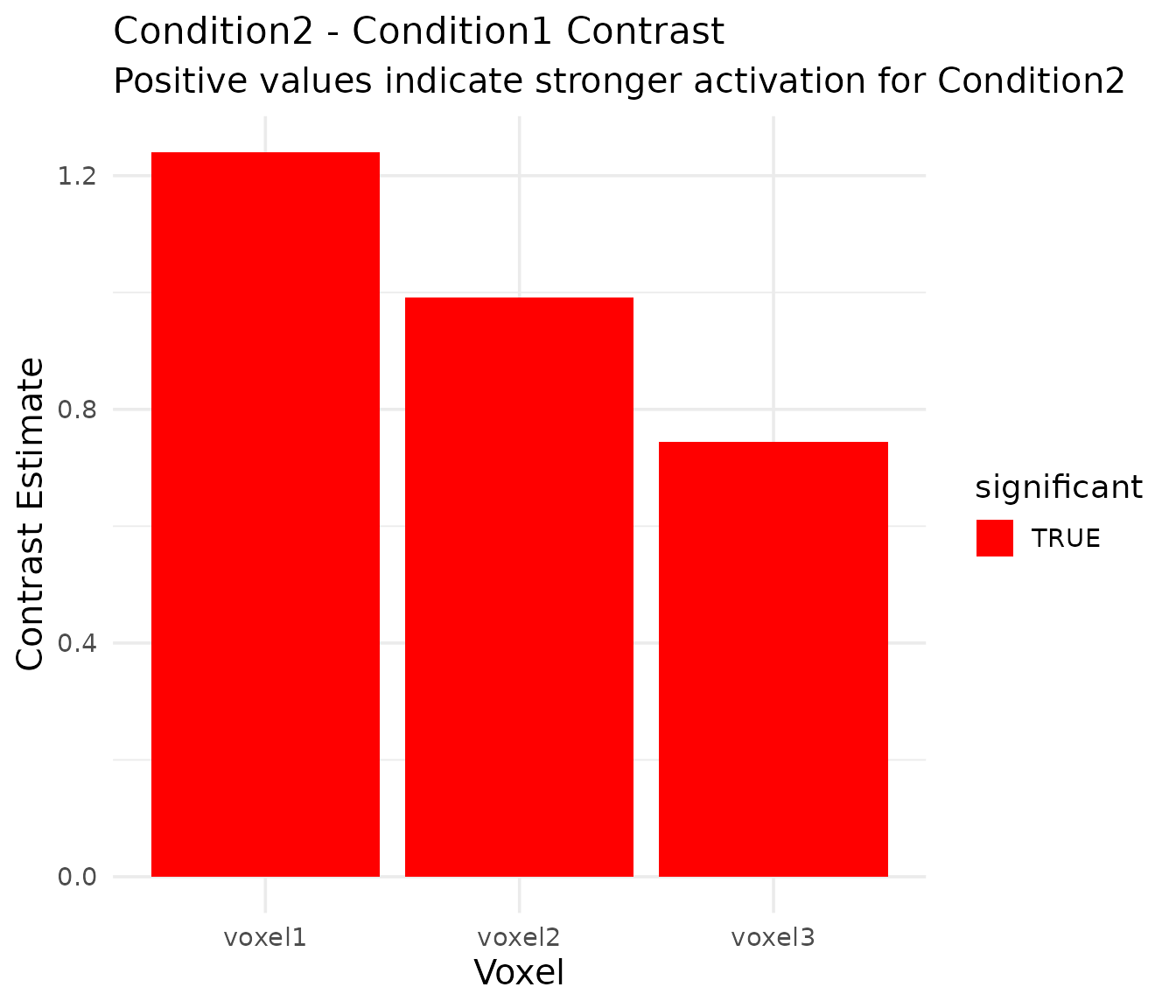

3. Contrasts Between Conditions

A key advantage of the GLM approach is the ability to directly compare conditions using contrasts.

# Define a contrast specification for comparing condition2 vs condition1

con_spec <- pair_contrast(~ condition == "condition2", ~ condition == "condition1", name = "cond2_minus_cond1")

# Define a contrast model using the specified contrast in hrf()

contrast_model <- fmri_lm(

formula = onset ~ hrf(condition, contrasts = con_spec),

block = ~ run,

dataset = dataset,

strategy = "chunkwise",

nchunks = 1

)

# Extract contrast results using tidy helper

contrast_results <- tidy(contrast_model, type = "contrasts") %>%

filter(term == "cond2_minus_cond1") %>%

mutate(

voxel = paste0("voxel", voxel),

significant = p_value < 0.05

)

# Display contrast results

kable(contrast_results, caption = "Contrast results: condition2 - condition1", digits = 4)| voxel | term | estimate | std_error | statistic | p_value | df_residual | significant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| voxel1 | cond2_minus_cond1 | 1.2398 | 0.1553 | 7.9826 | 0 | 194 | TRUE |

| voxel2 | cond2_minus_cond1 | 0.9918 | 0.1243 | 7.9826 | 0 | 194 | TRUE |

| voxel3 | cond2_minus_cond1 | 0.7439 | 0.0932 | 7.9826 | 0 | 194 | TRUE |

# Visualize the contrast

ggplot(contrast_results, aes(x = as.factor(voxel), y = estimate, fill = significant)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.title = element_text(size = 15),

plot.title = element_text(size = 16),

plot.subtitle = element_text(size = 15)) +

labs(title = "Condition2 - Condition1 Contrast",

subtitle = "Positive values indicate stronger activation for Condition2",

x = "Voxel",

y = "Contrast Estimate") +

scale_fill_manual(values = c("FALSE" = "gray", "TRUE" = "red"))

The contrast results show that Condition2 consistently elicits significantly stronger activation than Condition1 across all voxels, which matches our simulation parameters (where Condition2 had twice the amplitude of Condition1).

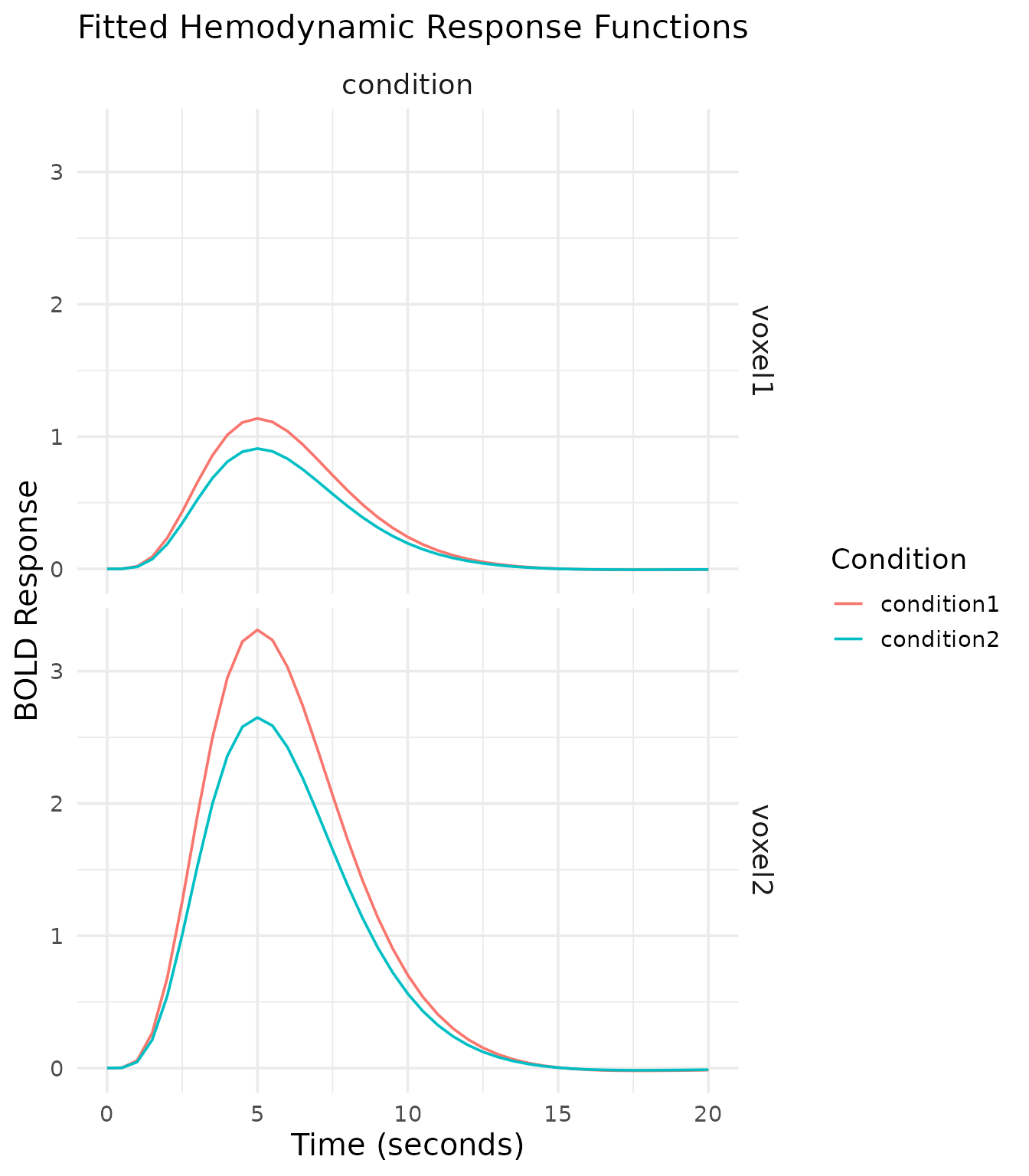

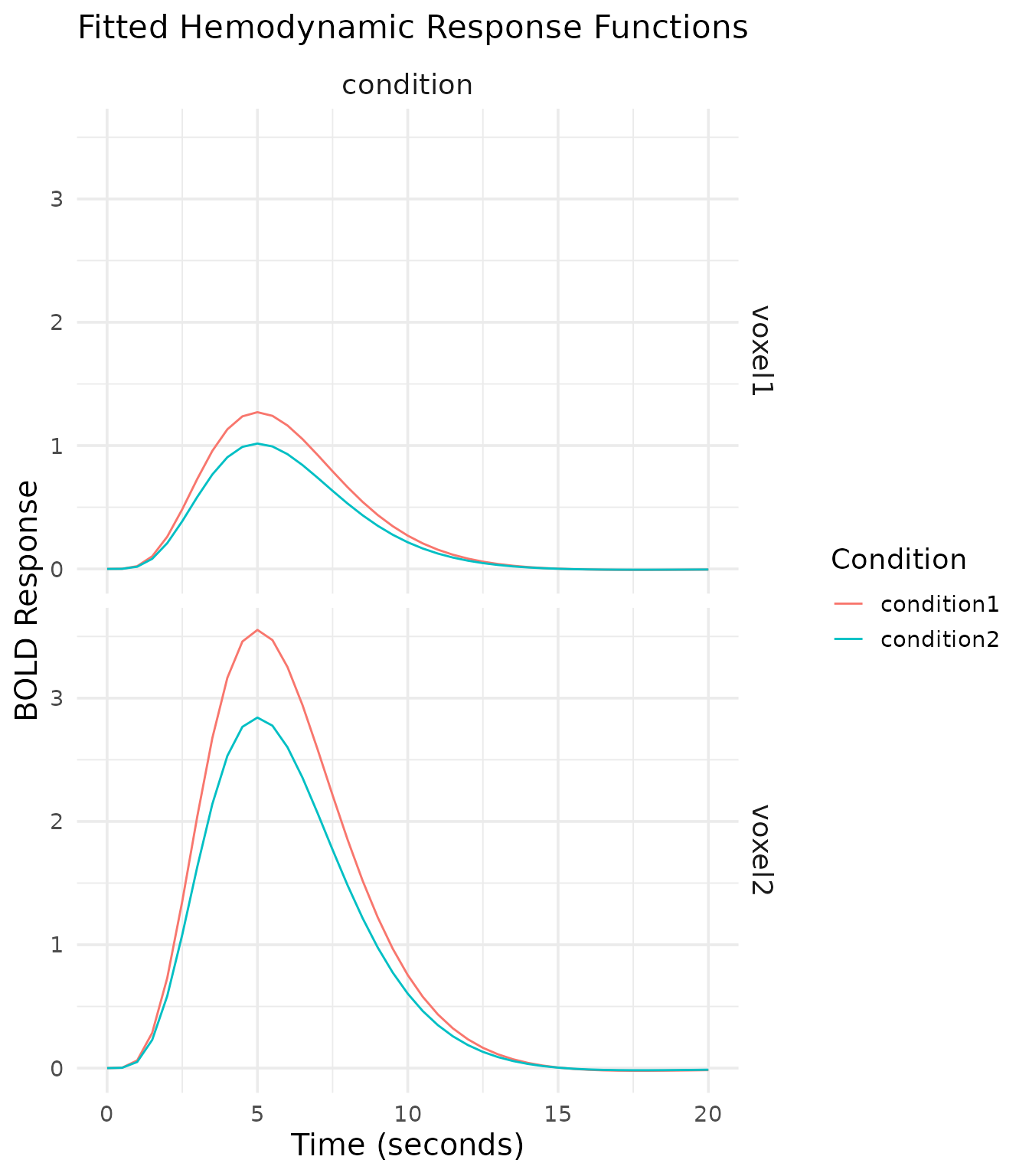

Fitted HRF Curves

Another useful visualization is the fitted hemodynamic response for each condition. This shows the estimated BOLD response over time.

# Extract fitted HRF curves from the fitted model

fitted_hrfs <- fitted_hrf(model, sample_at = seq(0, 20, by = 0.5))

# Extract the design info and reorganize for plotting

hrf_data <- lapply(names(fitted_hrfs), function(term) {

hrf_info <- fitted_hrfs[[term]]

design_info <- hrf_info$design

pred_values <- hrf_info$pred

# Combine with design info

result <- cbind(design_info, pred_values)

result$term <- term

return(result)

})

# Combine all HRF data

hrf_df <- do.call(rbind, hrf_data)

# Identify predicted-value columns by excluding known design columns

design_cols <- union(colnames(fitted_hrfs[[1]]$design), c("term"))

pred_cols <- setdiff(colnames(hrf_df), design_cols)

if (length(pred_cols) == 0) {

# Fallback: match common default names for matrix columns

pred_cols <- grep("^(V|X)?[0-9]+$|^pred.*$", colnames(hrf_df), value = TRUE)

}

# Create a data frame in long format for plotting

hrf_long <- hrf_df %>%

tidyr::pivot_longer(

cols = all_of(pred_cols),

names_to = "voxel_id",

values_to = "response"

) %>%

mutate(

voxel_index = suppressWarnings(as.integer(gsub("^[^0-9]*", "", voxel_id))),

voxel = paste0("voxel", voxel_index)

)

# Plot the fitted HRF curves for each condition and voxel

ggplot(hrf_long, aes(x = time, y = response, color = condition)) +

geom_line() +

facet_grid(voxel ~ term) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.title = element_text(size = 15),

plot.title = element_text(size = 16),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14)) +

labs(title = "Fitted Hemodynamic Response Functions",

x = "Time (seconds)",

y = "BOLD Response",

color = "Condition")

The fitted HRF curves show the temporal profile of the BOLD response for each condition. We can observe:

- The peak response around 5-6 seconds post-stimulus

- The stronger response for Condition2 compared to Condition1

- The decreasing response amplitude across voxels

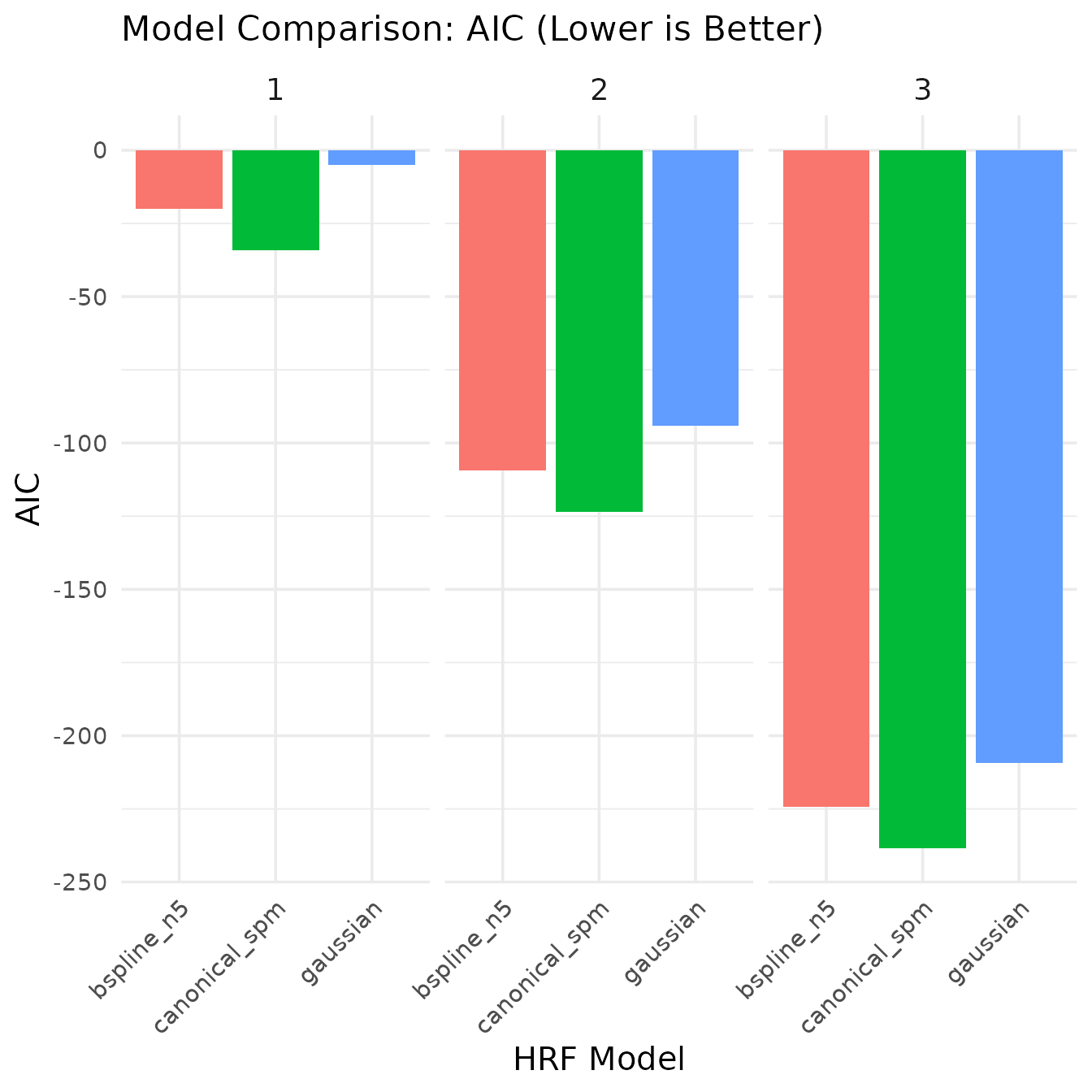

Comparing Models with Different HRF Bases

The choice of hemodynamic response function can impact model fit. Let’s compare different HRF options.

# Fit models with different HRF bases

model_canonical <- fmri_lm(

formula = onset ~ hrf(condition, basis = "spmg1"),

block = ~ run,

dataset = dataset,

strategy = "chunkwise",

nchunks = 1

)

model_gaussian <- fmri_lm(

formula = onset ~ hrf(condition, basis = "gaussian"),

block = ~ run,

dataset = dataset,

strategy = "chunkwise",

nchunks = 1

)

model_bspline <- fmri_lm(

formula = onset ~ hrf(condition, basis = "bspline", nbasis = 5),

block = ~ run,

dataset = dataset,

strategy = "chunkwise",

nchunks = 1

)

# Function to extract model fit statistics

extract_model_stats <- function(model, model_name, dataset) {

# Get observed data

observed_data <- get_data_matrix(dataset)

# Get design matrix (ensure it's a numeric matrix)

design_mat <- as.matrix(design_matrix(model$model))

# Get estimated coefficients (include baseline)

# Get all coefficients including baseline

betas <- as.matrix(coef(model, include_baseline = TRUE))

# Calculate fitted values

fitted_vals <- design_mat %*% t(betas)

# Calculate residuals

resids <- observed_data - fitted_vals

# Calculate sum of squared residuals

ssr <- colSums(resids^2)

# Calculate R-squared

tss <- apply(observed_data, 2, function(y) sum((y - mean(y))^2))

r_squared <- 1 - ssr/tss

# Calculate AIC

n <- nrow(observed_data)

p <- ncol(design_mat)

aic <- n * log(ssr/n) + 2 * p

# Return results

data.frame(

model = model_name,

voxel = 1:ncol(observed_data),

r_squared = r_squared,

aic = aic,

ssr = ssr

)

}

# Extract statistics for each model

stats_canonical <- extract_model_stats(model_canonical, "canonical_spm", dataset)

stats_gaussian <- extract_model_stats(model_gaussian, "gaussian", dataset)

stats_bspline <- extract_model_stats(model_bspline, "bspline_n5", dataset)

# Combine results

model_comparison <- rbind(stats_canonical, stats_gaussian, stats_bspline)

# Display model comparison

kable(model_comparison, caption = "Model comparison statistics", digits = 4)| model | voxel | r_squared | aic | ssr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| canonical_spm | 1 | 0.6500 | -34.1792 | 158.7644 |

| canonical_spm | 2 | 0.6500 | -123.4367 | 101.6092 |

| canonical_spm | 3 | 0.6500 | -238.5095 | 57.1552 |

| gaussian | 1 | 0.5950 | -4.9647 | 183.7349 |

| gaussian | 2 | 0.5950 | -94.2221 | 117.5903 |

| gaussian | 3 | 0.5950 | -209.2949 | 66.1446 |

| bspline_n5 | 1 | 0.6533 | -20.0520 | 157.2847 |

| bspline_n5 | 2 | 0.6533 | -109.3094 | 100.6622 |

| bspline_n5 | 3 | 0.6533 | -224.3822 | 56.6225 |

# Reshape for plotting

model_comparison_long <- model_comparison %>%

pivot_longer(cols = c(r_squared, aic, ssr), names_to = "metric", values_to = "value")

# Plot comparison (separate plots for different metrics)

ggplot(subset(model_comparison_long, metric == "r_squared"),

aes(x = model, y = value, fill = model)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

facet_wrap(~voxel, ncol = 3) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.title = element_text(size = 15),

plot.title = element_text(size = 16),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1),

legend.position = "none") +

labs(title = "Model Comparison: R-Squared",

x = "HRF Model",

y = "R-Squared")

ggplot(subset(model_comparison_long, metric == "aic"),

aes(x = model, y = value, fill = model)) +

geom_bar(stat = "identity") +

facet_wrap(~voxel, ncol = 3) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 14) +

theme(text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.title = element_text(size = 15),

plot.title = element_text(size = 16),

strip.text = element_text(size = 14),

axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 45, hjust = 1),

legend.position = "none") +

labs(title = "Model Comparison: AIC (Lower is Better)",

x = "HRF Model",

y = "AIC")

The model comparison shows:

- R-Squared: The proportion of variance explained by each model. Higher values indicate better fit.

- AIC (Akaike Information Criterion): A measure of model quality that balances goodness of fit with model complexity. Lower values indicate better models.

In this case, the canonical (SPM) model actually provides the best fit according to AIC, showing the lowest AIC values across voxels. This is an interesting result since we used the same HRF (SPMG1) to generate our data, confirming that the model selection correctly identifies the true underlying signal generator. The B-spline model, despite having more flexibility to capture variations in the signal, is penalized by AIC for its additional complexity. This demonstrates how model selection criteria like AIC can help identify the most parsimonious model that explains the data.

The canonical SPM model performs well due to its accurate representation of the hemodynamic response shape in our simulated data, making it the optimal choice for this particular dataset. This highlights the importance of selecting an appropriate HRF basis function when analyzing fMRI data.

Summary

This vignette demonstrated the complete workflow for fMRI linear

model analysis using the fmrireg package:

- Creating/simulating a dataset with realistic signal and noise properties

- Fitting linear models with different HRF options

- Extracting and visualizing model coefficients and statistics

- Computing and testing contrasts between conditions

- Comparing model performance using goodness-of-fit metrics

- Diagnosing model quality through residual analysis

The fmri_lm function provides a powerful and flexible

framework for analyzing fMRI data, with features for handling temporal

autocorrelation, modeling different HRF shapes, and computing contrasts

between conditions.

For more advanced analyses, you might consider: - Adding nuisance regressors to model physiological noise, motion, or other confounds - Using more complex experimental designs with multiple factors - Implementing spatial smoothing or other preprocessing steps - Extending the GLM with methods like psychophysiological interactions (PPI) or finite impulse response (FIR) models